CSE230 Slides 01: Lambda Calculus

Excerpt

UCSD CSE 230

Your Favorite Language

Probably has lots of features:

- Assignment (

x = x + 1) - Booleans, integers, characters, strings, …

- Conditionals

- Loops

return,break,continue- Functions

- Recursion

- References / pointers

- Objects and classes

- Inheritance

- …

Which ones can we do without?

What is the smallest universal language?

What is computable?

Before 1930s

Informal notion of an effectively calculable function:

can be computed by a human with pen and paper, following an algorithm

1936: Formalization

What is the smallest universal language?

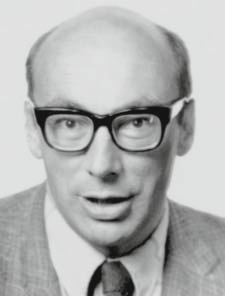

Alan Turing

Alonzo Church

The Next 700 Languages

Peter Landin

Whatever the next 700 languages turn out to be, they will surely be variants of lambda calculus.

Peter Landin, 1966

The Lambda Calculus

Has one feature:

- Functions

No, really

Assignment (x = x + 1)Booleans, integers, characters, strings, …ConditionalsLoopsreturn,break,continue- Functions

RecursionReferences / pointersObjects and classesInheritanceReflection

More precisely, only thing you can do is:

- Define a function

- Call a function

Describing a Programming Language

- Syntax: what do programs look like?

- Semantics: what do programs mean?

- Operational semantics: how do programs execute step-by-step?

Syntax: What Programs Look Like

e ::= x

| \x -> e

| e1 e2Programs are expressions e (also called λ-terms) of one of three kinds:

- Variable

x,y,z

- Abstraction (aka nameless function definition)

\x -> exis the formal parameter,eis the body- “for any

xcomputee”

- Application (aka function call)

e1 e2e1is the function,e2is the argument- in your favorite language:

e1(e2)

(Here each of e, e1, e2 can itself be a variable, abstraction, or application)

Examples

\x -> x -- The identity function (id)

-- ("for any x compute x")

\x -> (\y -> y) -- A function that returns (id)

\f -> (f (\x -> x)) -- A function that applies its argument to id QUIZ

Which of the following terms are syntactically incorrect?

A. \(\x -> x) -> y

B. \x -> x x

C. \x -> x (y x)

D. A and C

E. all of the above

Examples

\x -> x -- The identity function

-- ("for any x compute x")

\x -> (\y -> y) -- A function that returns the identity function

\f -> f (\x -> x) -- A function that applies its argument

-- to the identity functionHow do I define a function with two arguments?

- e.g. a function that takes

xandyand returnsy?

\x -> (\y -> y) -- A function that returns the identity function

-- OR: a function that takes two arguments

-- and returns the second one!How do I apply a function to two arguments?

- e.g. apply

\x -> (\y -> y)toappleandbanana?

(((\x -> (\y -> y)) apple) banana) -- first apply to apple,

-- then apply the result to bananaSyntactic Sugar

instead of

we write

\x -> (\y -> (\z -> e))

\x -> \y -> \z -> e

\x -> \y -> \z -> e

\x y z -> e

(((e1 e2) e3) e4)

e1 e2 e3 e4

\x y -> y -- A function that that takes two arguments

-- and returns the second one...

(\x y -> y) apple banana -- ... applied to two argumentsSemantics : What Programs Mean

How do I “run” / “execute” a λ-term?

Think of middle-school algebra:

-- Simplify expression:

(1 + 2) * ((3 * 8) - 2)

=

3 * ((3 * 8) - 2)

=

3 * ( 24 - 2)

=

3 * 22

=

66Execute = rewrite step-by-step

- Following simple rules

- until no more rules apply

Rewrite Rules of Lambda Calculus

- β-step (aka function call)

- α-step (aka renaming formals)

But first we have to talk about scope

Semantics: Scope of a Variable

The part of a program where a variable is visible

In the expression \x -> e

-

xis the newly introduced variable -

eis the scope ofx -

any occurrence of

xin\x -> eis bound (by the binder\x)

For example, x is bound in:

An occurrence of x in e is free if it’s not bound by an enclosing abstraction

For example, x is free in:

x y -- no binders at all!

\y -> x y -- no \x binder

(\x -> \y -> y) x -- x is outside the scope of the \x binder;

-- intuition: it's not "the same" xQUIZ

In the expression (\x -> x) x, is x bound or free?

A. first occurrence is bound, second is bound

B. first occurrence is bound, second is free

C. first occurrence is free, second is bound

D. first occurrence is free, second is free

EXERCISE: Free Variables

An variable x is free in e if there exists a free occurrence of x in e

We can formally define the set of all free variables in a term like so:

FV(x) = ???

FV(\x -> e) = ???

FV(e1 e2) = ???Closed Expressions

If e has no free variables it is said to be closed

- Closed expressions are also called combinators

What is the shortest closed expression?

Rewrite Rules of Lambda Calculus

- β-step (aka function call)

- α-step (aka renaming formals)

Semantics: Redex

A redex is a term of the form

A function (\x -> e1)

xis the parametere1is the returned expression

Applied to an argument e2

e2is the argument

Semantics: β-Reduction

A redex b-steps to another term …

(\x -> e1) e2 =b> e1[x := e2]where e1[x := e2] means

“e1 with all free occurrences of x replaced with e2”

Computation by search-and-replace:

-

If you see an abstraction applied to an argument, take the body of the abstraction and replace all free occurrences of the formal by that argument

-

We say that

(\x -> e1) e2β-steps toe1[x := e2]

Redex Examples

(\x -> x) apple

=b> appleIs this right? Ask Elsa!

QUIZ

(\x -> (\y -> y)) apple

=b> ???A. apple

B. \y -> apple

C. \x -> apple

D. \y -> y

E. \x -> y

QUIZ

(\x -> y x y x) apple

=b> ???A. apple apple apple apple

B. y apple y apple

C. y y y y

D. apple

QUIZ

(\x -> x (\x -> x)) apple

=b> ???A. apple (\x -> x)

B. apple (\apple -> apple)

C. apple (\x -> apple)

D. apple

E. \x -> x

EXERCISE

What is a λ-term fill_this_in such that

fill_this_in apple

=b> bananaELSA: https://goto.ucsd.edu/elsa/index.html

Click here to try this exercise

A Tricky One

(\x -> (\y -> x)) y

=b> \y -> yIs this right?

Something is Fishy

(\x -> (\y -> x)) y

=b> \y -> yIs this right?

Problem: The free y in the argument has been captured by \y in body!

Solution: Ensure that formals in the body are different from free-variables of argument!

Capture-Avoiding Substitution

We have to fix our definition of β-reduction:

(\x -> e1) e2 =b> e1[x := e2]where e1[x := e2] means “e1 with all free occurrences of x replaced with e2”

e1with all free occurrences ofxreplaced withe2- as long as no free variables of

e2get captured

Formally:

x[x := e] = e

y[x := e] = y -- as x /= y

(e1 e2)[x := e] = (e1[x := e]) (e2[x := e])

(\x -> e1)[x := e] = \x -> e1 -- Q: Why leave `e1` unchanged?

(\y -> e1)[x := e]

| not (y in FV(e)) = \y -> e1[x := e]Oops, but what to do if y is in the free-variables of e?

- i.e. if

\y -> ...may capture those free variables?

Rewrite Rules of Lambda Calculus

- β-step (aka function call)

- α-step (aka renaming formals)

Semantics: α-Renaming

\x -> e =a> \y -> e[x := y]

where not (y in FV(e))-

We rename a formal parameter

xtoy -

By replace all occurrences of

xin the body withy -

We say that

\x -> eα-steps to\y -> e[x := y]

Example:

\x -> x =a> \y -> y =a> \z -> zAll these expressions are α-equivalent

What’s wrong with these?

-- (A)

\f -> f x =a> \x -> x x-- (B)

(\x -> \y -> y) y =a> (\x -> \z -> z) zTricky Example Revisited

(\x -> (\y -> x)) y

-- rename 'y' to 'z' to avoid capture

=a> (\x -> (\z -> x)) y

-- now do b-step without capture!

=b> \z -> yTo avoid getting confused,

-

you can always rename formals,

-

so different variables have different names!

Normal Forms

Recall redex is a λ-term of the form

(\x -> e1) e2

A λ-term is in normal form if it contains no redexes.

QUIZ

Which of the following term are not in normal form ?

A. x

B. x y

C. (\x -> x) y

D. x (\y -> y)

E. C and D

Semantics: Evaluation

A λ-term e evaluates to e' if

- There is a sequence of steps

e =?> e_1 =?> ... =?> e_N =?> e'where each =?> is either =a> or =b> and N >= 0

e'is in normal form

Examples of Evaluation

(\x -> x) apple

=b> apple(\f -> f (\x -> x)) (\x -> x)

=?> ???(\x -> x x) (\x -> x)

=?> ???Elsa shortcuts

Named λ-terms:

let ID = \x -> x -- abbreviation for \x -> xTo substitute name with its definition, use a =d> step:

ID apple

=d> (\x -> x) apple -- expand definition

=b> apple -- beta-reduceEvaluation:

e1 =*> e2:e1reduces toe2in 0 or more steps- where each step is

=a>,=b>, or=d>

- where each step is

e1 =~> e2:e1evaluates toe2ande2is in normal form

EXERCISE

Fill in the definitions of FIRST, SECOND and THIRD such that you get the following behavior in elsa

let FIRST = fill_this_in

let SECOND = fill_this_in

let THIRD = fill_this_in

eval ex1 :

FIRST apple banana orange

=*> apple

eval ex2 :

SECOND apple banana orange

=*> banana

eval ex3 :

THIRD apple banana orange

=*> orangeELSA: https://goto.ucsd.edu/elsa/index.html

Click here to try this exercise

Non-Terminating Evaluation

(\x -> x x) (\x -> x x)

=b> (\x -> x x) (\x -> x x)Some programs loop back to themselves…

… and never reduce to a normal form!

This combinator is called Ω

What if we pass Ω as an argument to another function?

let OMEGA = (\x -> x x) (\x -> x x)

(\x -> (\y -> y)) OMEGADoes this reduce to a normal form? Try it at home!

Programming in λ-calculus

Real languages have lots of features

- Booleans

- Records (structs, tuples)

- Numbers

- Functions [we got those]

- Recursion

Lets see how to encode all of these features with the λ-calculus.

λ-calculus: Booleans

How can we encode Boolean values (TRUE and FALSE) as functions?

Well, what do we do with a Boolean b?

Make a binary choice

if b then e1 else e2

Booleans: API

We need to define three functions

let TRUE = ???

let FALSE = ???

let ITE = \b x y -> ??? -- if b then x else ysuch that

ITE TRUE apple banana =~> apple

ITE FALSE apple banana =~> banana(Here, let NAME = e means NAME is an abbreviation for e)

Booleans: Implementation

let TRUE = \x y -> x -- Returns its first argument

let FALSE = \x y -> y -- Returns its second argument

let ITE = \b x y -> b x y -- Applies condition to branches

-- (redundant, but improves readability)Example: Branches step-by-step

eval ite_true:

ITE TRUE e1 e2

=d> (\b x y -> b x y) TRUE e1 e2 -- expand def ITE

=b> (\x y -> TRUE x y) e1 e2 -- beta-step

=b> (\y -> TRUE e1 y) e2 -- beta-step

=b> TRUE e1 e2 -- expand def TRUE

=d> (\x y -> x) e1 e2 -- beta-step

=b> (\y -> e1) e2 -- beta-step

=b> e1Example: Branches step-by-step

Now you try it!

Can you fill in the blanks to make it happen?

eval ite_false:

ITE FALSE e1 e2

-- fill the steps in!

=b> e2 EXERCISE: Boolean Operators

ELSA: https://goto.ucsd.edu/elsa/index.html Click here to try this exercise

Now that we have ITE it’s easy to define other Boolean operators:

let NOT = \b -> ???

let OR = \b1 b2 -> ???

let AND = \b1 b2 -> ???When you are done, you should get the following behavior:

eval ex_not_t:

NOT TRUE =*> FALSE

eval ex_not_f:

NOT FALSE =*> TRUE

eval ex_or_ff:

OR FALSE FALSE =*> FALSE

eval ex_or_ft:

OR FALSE TRUE =*> TRUE

eval ex_or_ft:

OR TRUE FALSE =*> TRUE

eval ex_or_tt:

OR TRUE TRUE =*> TRUE

eval ex_and_ff:

AND FALSE FALSE =*> FALSE

eval ex_and_ft:

AND FALSE TRUE =*> FALSE

eval ex_and_ft:

AND TRUE FALSE =*> FALSE

eval ex_and_tt:

AND TRUE TRUE =*> TRUEProgramming in λ-calculus

- Booleans [done]

- Records (structs, tuples)

- Numbers

- Functions [we got those]

- Recursion

λ-calculus: Records

Let’s start with records with two fields (aka pairs)

What do we do with a pair?

- Pack two items into a pair, then

- Get first item, or

- Get second item.

Pairs : API

We need to define three functions

let PAIR = \x y -> ??? -- Make a pair with elements x and y

-- { fst : x, snd : y }

let FST = \p -> ??? -- Return first element

-- p.fst

let SND = \p -> ??? -- Return second element

-- p.sndsuch that

eval ex_fst:

FST (PAIR apple banana) =*> apple

eval ex_snd:

SND (PAIR apple banana) =*> bananaPairs: Implementation

A pair of x and y is just something that lets you pick between x and y! (i.e. a function that takes a boolean and returns either x or y)

let PAIR = \x y -> (\b -> ITE b x y)

let FST = \p -> p TRUE -- call w/ TRUE, get first value

let SND = \p -> p FALSE -- call w/ FALSE, get second valueEXERCISE: Triples

How can we implement a record that contains three values?

ELSA: https://goto.ucsd.edu/elsa/index.html

Click here to try this exercise

let TRIPLE = \x y z -> ???

let FST3 = \t -> ???

let SND3 = \t -> ???

let THD3 = \t -> ???

eval ex1:

FST3 (TRIPLE apple banana orange)

=*> apple

eval ex2:

SND3 (TRIPLE apple banana orange)

=*> banana

eval ex3:

THD3 (TRIPLE apple banana orange)

=*> orangeProgramming in λ-calculus

- Booleans [done]

- Records (structs, tuples) [done]

- Numbers

- Functions [we got those]

- Recursion

λ-calculus: Numbers

Let’s start with natural numbers (0, 1, 2, …)

What do we do with natural numbers?

- Count:

0,inc - Arithmetic:

dec,+,-,* - Comparisons:

==,<=, etc

Natural Numbers: API

We need to define:

- A family of numerals:

ZERO,ONE,TWO,THREE, … - Arithmetic functions:

INC,DEC,ADD,SUB,MULT - Comparisons:

IS_ZERO,EQ

Such that they respect all regular laws of arithmetic, e.g.

IS_ZERO ZERO =~> TRUE

IS_ZERO (INC ZERO) =~> FALSE

INC ONE =~> TWO

...Natural Numbers: Implementation

Church numerals: a number N is encoded as a combinator that calls a function on an argument N times

let ONE = \f x -> f x

let TWO = \f x -> f (f x)

let THREE = \f x -> f (f (f x))

let FOUR = \f x -> f (f (f (f x)))

let FIVE = \f x -> f (f (f (f (f x))))

let SIX = \f x -> f (f (f (f (f (f x)))))

...QUIZ: Church Numerals

Which of these is a valid encoding of ZERO ?

-

A:

let ZERO = \f x -> x -

B:

let ZERO = \f x -> f -

C:

let ZERO = \f x -> f x -

D:

let ZERO = \x -> x -

E: None of the above

Does this function look familiar?

λ-calculus: Increment

-- Call `f` on `x` one more time than `n` does

let INC = \n -> (\f x -> ???)Example:

eval inc_zero :

INC ZERO

=d> (\n f x -> f (n f x)) ZERO

=b> \f x -> f (ZERO f x)

=*> \f x -> f x

=d> ONEEXERCISE

Fill in the implementation of ADD so that you get the following behavior

Click here to try this exercise

let ZERO = \f x -> x

let ONE = \f x -> f x

let TWO = \f x -> f (f x)

let INC = \n f x -> f (n f x)

let ADD = fill_this_in

eval add_zero_zero:

ADD ZERO ZERO =~> ZERO

eval add_zero_one:

ADD ZERO ONE =~> ONE

eval add_zero_two:

ADD ZERO TWO =~> TWO

eval add_one_zero:

ADD ONE ZERO =~> ONE

eval add_one_zero:

ADD ONE ONE =~> TWO

eval add_two_zero:

ADD TWO ZERO =~> TWO QUIZ

How shall we implement ADD?

A. let ADD = \n m -> n INC m

B. let ADD = \n m -> INC n m

C. let ADD = \n m -> n m INC

D. let ADD = \n m -> n (m INC)

E. let ADD = \n m -> n (INC m)

λ-calculus: Addition

-- Call `f` on `x` exactly `n + m` times

let ADD = \n m -> n INC mExample:

eval add_one_zero :

ADD ONE ZERO

=~> ONEQUIZ

How shall we implement MULT?

A. let MULT = \n m -> n ADD m

B. let MULT = \n m -> n (ADD m) ZERO

C. let MULT = \n m -> m (ADD n) ZERO

D. let MULT = \n m -> n (ADD m ZERO)

E. let MULT = \n m -> (n ADD m) ZERO

λ-calculus: Multiplication

-- Call `f` on `x` exactly `n * m` times

let MULT = \n m -> n (ADD m) ZEROExample:

eval two_times_three :

MULT TWO ONE

=~> TWOProgramming in λ-calculus

- Booleans [done]

- Records (structs, tuples) [done]

- Numbers [done]

- Lists

- Functions [we got those]

- Recursion

λ-calculus: Lists

Lets define an API to build lists in the λ-calculus.

An Empty List

Constructing a list

A list with 4 elements

CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL)))intuitively CONS h t creates a new list with

- head

h - tail

t

Destructing a list

HEAD lreturns the first element of the listTAIL lreturns the rest of the list

HEAD (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL))))

=~> apple

TAIL (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL))))

=~> CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL)))λ-calculus: Lists

let NIL = ???

let CONS = ???

let HEAD = ???

let TAIL = ???

eval exHd:

HEAD (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL))))

=~> apple

eval exTl

TAIL (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL))))

=~> CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe (CONS dragon NIL)))EXERCISE: Nth

Write an implementation of GetNth such that

GetNth n lreturns the n-th element of the listl

Assume that l has n or more elements

let GetNth = ???

eval nth1 :

GetNth ZERO (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe NIL)))

=~> apple

eval nth1 :

GetNth ONE (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe NIL)))

=~> banana

eval nth2 :

GetNth TWO (CONS apple (CONS banana (CONS cantaloupe NIL)))

=~> cantaloupeClick here to try this in elsa

λ-calculus: Recursion

I want to write a function that sums up natural numbers up to n:

let SUM = \n -> ... -- 0 + 1 + 2 + ... + nsuch that we get the following behavior

eval exSum0: SUM ZERO =~> ZERO

eval exSum1: SUM ONE =~> ONE

eval exSum2: SUM TWO =~> THREE

eval exSum3: SUM THREE =~> SIXCan we write sum using Church Numerals?

Click here to try this in Elsa

QUIZ

You can write SUM using numerals but its tedious.

Is this a correct implementation of SUM?

let SUM = \n -> ITE (ISZ n)

ZERO

(ADD n (SUM (DEC n)))A. Yes

B. No

No!

- Named terms in Elsa are just syntactic sugar

- To translate an Elsa term to λ-calculus: replace each name with its definition

\n -> ITE (ISZ n)

ZERO

(ADD n (SUM (DEC n))) -- But SUM is not yet defined!Recursion:

- Inside this function

- Want to call the same function on

DEC n

Looks like we can’t do recursion!

- Requires being able to refer to functions by name,

- But λ-calculus functions are anonymous.

Right?

λ-calculus: Recursion

Think again!

Recursion:

Instead of

- Inside this function I want to call the same function on

DEC n

Lets try

- Inside this function I want to call some function

reconDEC n - And BTW, I want

recto be the same function

Step 1: Pass in the function to call “recursively”

let STEP =

\rec -> \n -> ITE (ISZ n)

ZERO

(ADD n (rec (DEC n))) -- Call some recStep 2: Do some magic to STEP, so rec is itself

\n -> ITE (ISZ n) ZERO (ADD n (rec (DEC n)))That is, obtain a term MAGIC such that

λ-calculus: Fixpoint Combinator

Wanted: a λ-term FIX such that

FIX STEPcallsSTEPwithFIX STEPas the first argument:

(FIX STEP) =*> STEP (FIX STEP)(In math: a fixpoint of a function f(x) is a point x, such that f(x) = x)

Once we have it, we can define:

Then by property of FIX we have:

SUM =*> FIX STEP =*> STEP (FIX STEP) =*> STEP SUMand so now we compute:

eval sum_two:

SUM TWO

=*> STEP SUM TWO

=*> ITE (ISZ TWO) ZERO (ADD TWO (SUM (DEC TWO)))

=*> ADD TWO (SUM (DEC TWO))

=*> ADD TWO (SUM ONE)

=*> ADD TWO (STEP SUM ONE)

=*> ADD TWO (ITE (ISZ ONE) ZERO (ADD ONE (SUM (DEC ONE))))

=*> ADD TWO (ADD ONE (SUM (DEC ONE)))

=*> ADD TWO (ADD ONE (SUM ZERO))

=*> ADD TWO (ADD ONE (ITE (ISZ ZERO) ZERO (ADD ZERO (SUM DEC ZERO)))

=*> ADD TWO (ADD ONE (ZERO))

=*> THREEHow should we define FIX???

The Y combinator

Remember Ω?

(\x -> x x) (\x -> x x)

=b> (\x -> x x) (\x -> x x)This is self-replcating code! We need something like this but a bit more involved…

The Y combinator discovered by Haskell Curry:

let FIX = \stp -> (\x -> stp (x x)) (\x -> stp (x x))How does it work?

eval fix_step:

FIX STEP

=d> (\stp -> (\x -> stp (x x)) (\x -> stp (x x))) STEP

=b> (\x -> STEP (x x)) (\x -> STEP (x x))

=b> STEP ((\x -> STEP (x x)) (\x -> STEP (x x)))

-- ^^^^^^^^^^ this is FIX STEP ^^^^^^^^^^^That’s all folks, Haskell Curry was very clever.

Next week: We’ll look at the language named after him (Haskell)